Four years ago, just hours after former President Donald Trump promised to pull the United States out of the Paris Agreement, the governors of California, Washington, and New York announced the formation of the “U.S. Climate Alliance” — a group of states committed to following through on the country’s broken promises. “If the president is going to be AWOL in this profoundly important human endeavor,” Governor Jerry Brown of California said at the time, “then California and other states will step up.”

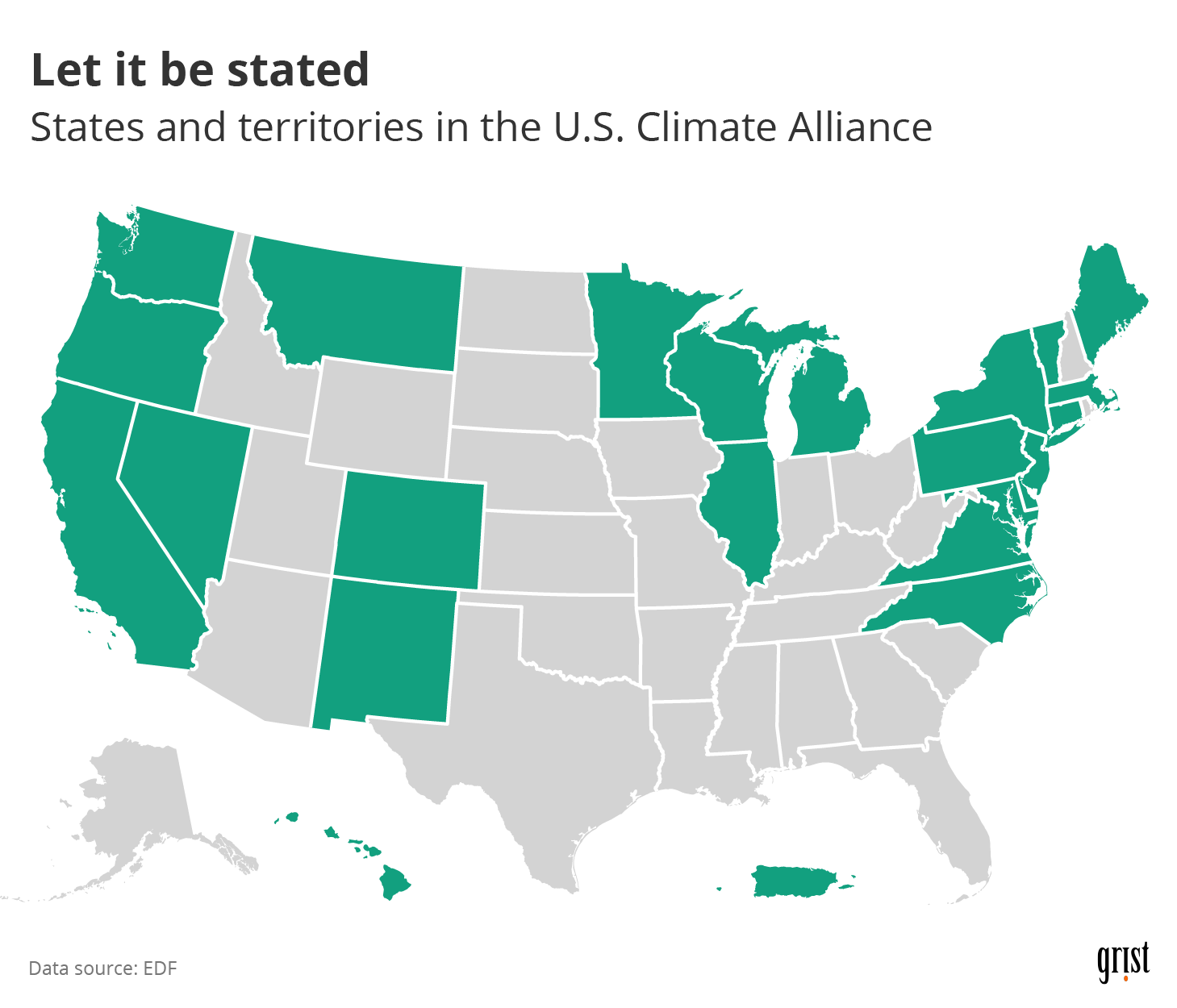

Today, the alliance boasts 24 states and one territory: Puerto Rico. All have vowed to collectively cut emissions 26 to 28 percent by 2025, compared to 2005 levels. Many have set ambitious goals to cover their states in wind turbines, electrify cars and trucks, and slash the amount of dangerous pollutants in the air. With President Joe Biden in the White House, and with the U.S. back in the Paris Agreement, hopes are high for action on the climate crisis. But the states’ struggles over the past four years demonstrate that it may be a long road ahead.

Most of the states that have promised sweeping emissions cuts by 2025 — which include the U.S. Climate Alliance members and the state of Louisiana — are still off-track to meet the U.S. commitment under the Paris Agreement, according to an analysis by the Environmental Defense Fund released last month. The study, based on data from the research firm Rhodium Group, found that if the country recovers fairly quickly from COVID-19, U.S. emissions in those states would only fall 18 percent by 2025, missing the goal of cutting emissions by 26 percent.

That’s not really the states’ fault. Over the past four years, governors and state legislators have been swimming against the tide, trying to pass legislation and issuing executive orders even as the Environmental Protection Agency and the president openly worked to block their efforts.

“I would say that states are doing as well as they can, given the difficult circumstances,” said Jeff Mauk, executive director of the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators. “They had a federal government that was hostile to their efforts to act on climate.”

In California, for example, Trump’s EPA revoked the state’s authority to set its own emissions standards for cars — throwing the car industry into disarray and also endangering fuel-economy standards in 12 other states. And in late 2019, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which oversees the transmission of electricity and the transport of oil, released a controversial rule that made new renewables more expensive and boosted coal production in 13 states.

“It really just felt like they were doing everything they could to block the transition to renewable energy,” Mauk said.

But the Environmental Defense Fund’s analysis also shows the limits of current state policies, according to Pam Kiely, the organization’s senior director of regulatory strategy. States have put a lot of effort into cutting emissions from power generation — getting renewables onto the grid, for example, or phasing out the burning of coal. But electricity only accounts for around 28 percent of the country’s CO2 emissions; that leaves a lot for states to work on outside the grid — the emissions that come from cars, steelmaking, or central heating. “Broadly speaking, climate action at the state level has sort of equated to action in the electric power sector,” Kiely said. “But we’ve got a lot to do in the transportation sector, in the built environment, in the industrial sector, and beyond.”

Kiely also points out that while states have big goals to cut carbon emissions, they haven’t always been able to set strict limits on carbon dioxide pollution that ratchet down over time — which she sees as the key to cutting emissions. Some of that is the result of prolonged pushback from conservatives. In Oregon, Republican state senators fled the Capitol in 2019 rather than vote on a landmark bill to cap carbon emissions across the economy. And just a few weeks ago in Massachusetts, Republican Governor Charlie Baker vetoed a massive climate change bill over concern that some of its interim goals — like a requirement to cut emissions in half by 2030, compared to 1990 levels — would be too costly to achieve.

The U.S. Climate Alliance, meanwhile, has disputed some of the Environmental Defense Fund’s findings, arguing that the inclusion of Louisiana (which has committed to the Paris Agreement’s goals, but is not an official member of the alliance) lowers overall projections for how much emissions can be cut by 2025. The alliance’s own analysis, released at the end of 2019, projected that member states would slash emissions 20 to 27 percent by 2025 — potentially meeting that Paris target of 26 percent.

The group opted not to make a similar projection at the end of last year, because of uncertainty around the coronavirus pandemic. While a quicker recovery could lead emissions to rebound, a slower economic recovery could get states much closer to their target, since recessions and pandemic-induced disasters tend to cut carbon emissions quickly.

Julie Cerqueira, the alliance’s executive director, said that without the group of states, the future of climate policy in the U.S. would look much darker. “If it wasn’t for these 25 states doing everything possible within their authority,” she said, “I think that we’d be starting from zero again.”

The alliance also notes that its member states have performed well in comparison to the states that didn’t commit to staying in the Paris Agreement. Between 2005 and 2018, states in the alliance cut their CO2 emissions by 14 percent; the other 26 states saw emissions fall by roughly 8 percent. These non-member states — which include oil-rich Texas, West Virginia, and Idaho — account for 60 percent of the country’s CO2 emissions. If they stay on their current course, their emissions could end up increasing over the next five to 10 years, according to a U.S. Climate Alliance report.

With the U.S. back in the Paris Agreement, Cerqueira says that alliance members are planning to continue their work during the Biden administration, partnering with the federal government instead of working against it. Representatives from member states have already met with Gina McCarthy, Biden’s new “climate czar,” to discuss future policies and plans.

Mauk, of the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators, expects states to expand their efforts to cut emissions during the Biden years. During the Obama administration, he argued, most policymakers hoped that Congress would pass sweeping legislation to take on climate change. Now, however, with only a slim Democratic majority in the Senate, governors and state legislators are unlikely to count on the federal government to solve all their climate problems. “People have learned the lessons from the last decade,” he said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline 25 states promised to stay in the Paris Agreement. Did they follow through? on Jan 27, 2021.