Ancient forest along the Salmon River, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

The Executive Order

On January 27, 2021, President Biden signed the Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad. [1] One aspect of that Order directed the Interior Department to formulate steps to achieve the President’s commitment to conserve at least 30% each of our lands and waters by 2030. The Interior Department issued a press release describing this process in more detail and referenced a U.S. Geological Survey report that only 12% of lands in the continental U.S. are permanently protected. [2] [3] Even those given the highest status of current protection such as wilderness areas and national parks are still subject to activities that degrade them from being truly protected. For example, livestock grazing continues in over a quarter of the 52 million acres of wilderness areas in the lower forty-eight states in the U.S. [4]

Our National Forests are further down the list and remain far from protected, being in the third of four levels of protection, the fourth level being no protection at all. According to the Executive Order, the Secretary of the Interior shall submit a report within 90 days proposing guidelines for determining whether lands and waters qualify for conservation. The USGS report stresses analyzing and setting aside migration corridors for species to prevent their extinction from the effects of climate change.

In 2010, the Forest Service produced a National Roadmap for Responding to Climate Change. [5] This roadmap provides guidance to the agency to: (1) Assess vulnerability of species and ecosystems to climate change, (2) Restore resilience, (3) Promote carbon sequestration, and (4) Connect habitats, restore important corridors for fish and wildlife, decrease fragmentation and remove impediments to species migration.

As advocates for restoring wildlife corridors and core areas, we have continued to insist on the Forest Service analyzing these corridors and their ability to function for the species of interest, whether it be deer, elk, Canada lynx, wolverine or grizzly bears. This entails use of the science-based habitat criteria required for these species and comparing this to the current habitat conditions in the corridor of interest. Then, the agency must adjust management to meet these conditions, such as reducing road density. To date, the Forest Service has ignored our request as pipelines, mines, timber and “forest health” projects continue to expand their footprint, while roads and noise and activity from off road vehicles are pervasive.

The Yellowstone to Uintas Connection

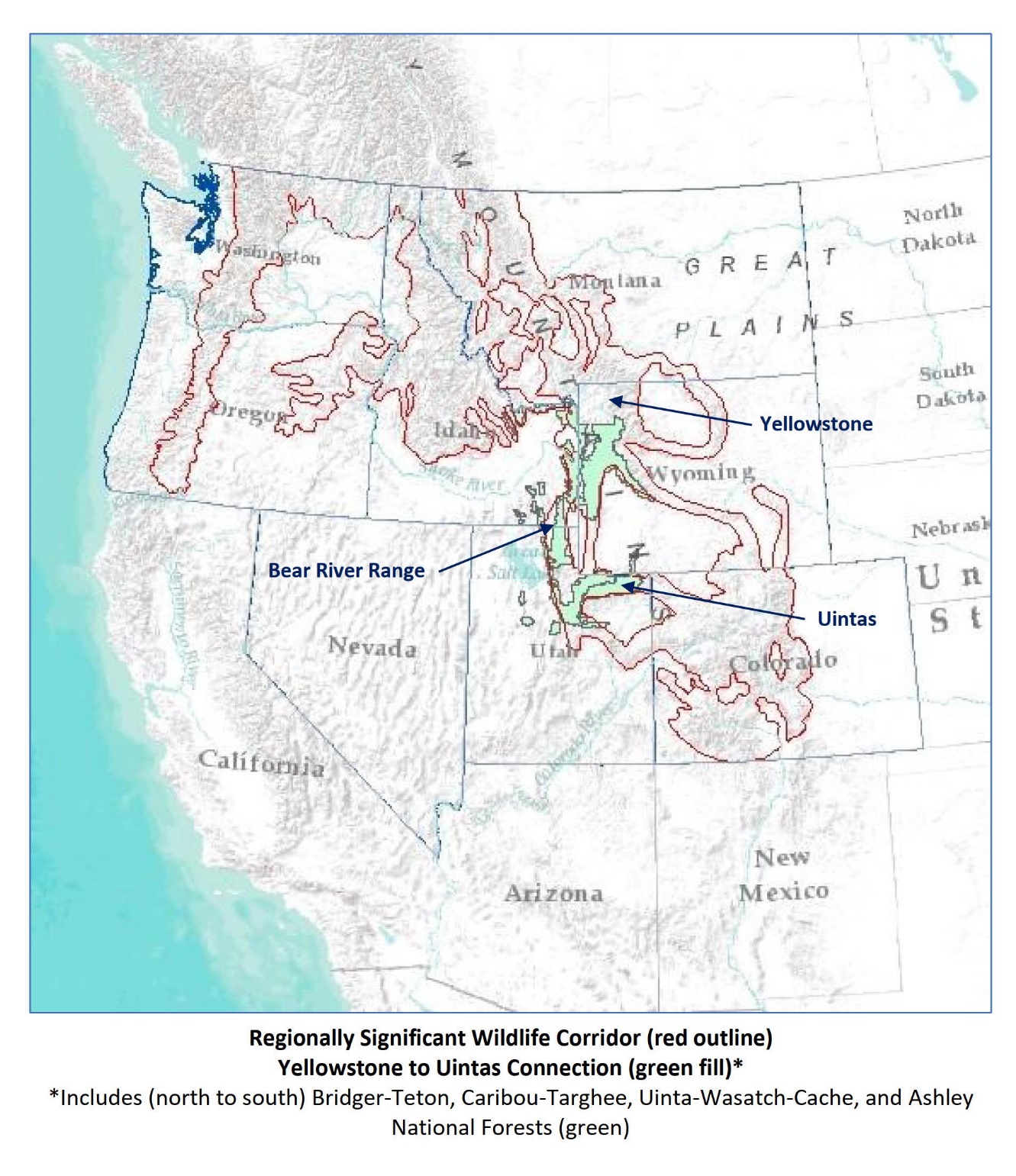

The Yellowstone to Uintas Connection is the high elevation wildlife corridor connecting the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and Northern Rockies to the High Uintas Wilderness and Southern Rockies. It is also the name of our non-profit organization. [6] The Corridor includes portions of several National Forests, including the Ashley, Bridger-Teton, Caribou-Targhee, and Uinta-Wasatch-Cache. It is a critical link in the larger Regionally Significant Wildlife Corridor designated by the Forest Service. [7] In the past, Canada lynx, wolverine, grizzly bear and other wildlife used this corridor and the associated core areas such as the High Uintas Wilderness. Today, these animals are absent from much of this former range. More details are available in our recent comments on Forest Service projects in the corridor. [8] [9]

Today, the Y2U Connection is heavily damaged and made non-functional for these animals and other native wildlife by a variety of human activities. Road densities exceed levels these animals can tolerate. Roads fragment the habitat and intrude even into areas designated as Inventoried Roadless Areas. [10] Phosphate mines and mountain top removal, pipelines, transmission lines, and timber harvest further fragment and destroy the habitat. [11]

Noise and disturbance from mining, recreational vehicles such as atvs, dirt bikes and side by sides drown out natures’ sounds in spring, summer and fall while in winter, groomed snowmobile trails dissect the mountains. Thus enabled, snowmobilers leave no place secure from their noise as they high mark remote slopes and many carry guns to kill wolves, coyotes and other carnivores, or “coyote whack”, a term used to describe chasing and running over coyotes with their machines. They can scout a hundred miles of groomed trails in a day looking for mountain lion tracks so they can turn their dogs loose, chase down and tree the lion and kill it.

Finally, the habitat destruction is made complete by the livestock grazing the Forest Service permits across the landscape. Entire Forests are divided into grazing allotments with fences, water troughs, pipelines, herders with guns to kill any bear, wolf, coyote or other carnivore they see “harassing” livestock. States are also doing their best to eliminate carnivores. For example, Idaho is now proposing no limits on killing mountain lions. [12]

The Forest Service does not address the activities fragmenting the corridor. At best, they will claim that animals will travel around the periphery of a project and use other habitat. That other habitat is not analyzed for its functionality for any species whether it’s deer, elk, sage grouse, lynx. wolverine or any other. On the rare occasion when road densities are considered, the analysis omits illegal, user-created routes, “closed” but not restored logging or other administrative roads that are still trespassed by atvs or hunters on foot, leading to continuing disturbance and loss of security habitat. Inventoried Roadless Areas in Idaho are divided into prescriptions allowing all extractive uses and are degraded by user-created roads, timber harvest, and sold off or traded for mining facilities.

Forest Service Restoration

In the past two years, in the corridor in SE Idaho and NE Utah, we have seen over 2,000,000 acres of “restoration” projects aimed at addressing the problems the Forest Service identifies as adversely affecting these Forests. They describe the problem as a departure from natural regimes of vegetation characteristics and fire frequency. These departures are attributed to past fire suppression, timber harvest, drought and livestock grazing. Generally, the stated purpose of these proposed projects is to improve big game habitat, reduce conifer encroachment in aspen and manage hazardous fuel accumulations. [13]

None of these projects propose to halt or reduce the activities that they claim to be causing these departures from historic or natural conditions, or that affect wildlife. They do not propose to limit timber harvest. They do not propose to terminate or reduce livestock grazing. They do not propose to close and restore roads to a natural state to achieve security habitat for wildlife. They also do not acknowledge the inability of fuels treatments to moderate severe fires as these are climate driven events. They do not propose to limit their logging, thinning and fuels reductions to areas immediately around structures as the science recommends, but instead propose to treat millions of acres remote from structures. [14] [15] [16]

The Bear River Range

The Bear River Range in the Caribou-Targhee and Wasatch-Cache National Forests in SE Idaho and NE Utah is a critical part of the Yellowstone to Uintas Connection. It is the place where the last grizzly bear, Old Ephraim, was killed in 1923 near Logan, Utah. You will not find grizzly bears here anymore. [17] The Bear River Range also has all the problems with habitat fragmentation by roads and extractive uses described for the corridor overall. Even the Caribou National Forest Revised Forest Plan in its FEIS admitted that road densities are excessive in the Bear River Range, yet they do not address this problem, instead they expand roads with each additional project. [18]

The Bear River Range in the Caribou-Targhee and Wasatch-Cache National Forests in SE Idaho and NE Utah is a critical part of the Yellowstone to Uintas Connection. It is the place where the last grizzly bear, Old Ephraim, was killed in 1923 near Logan, Utah. You will not find grizzly bears here anymore. [17] The Bear River Range also has all the problems with habitat fragmentation by roads and extractive uses described for the corridor overall. Even the Caribou National Forest Revised Forest Plan in its FEIS admitted that road densities are excessive in the Bear River Range, yet they do not address this problem, instead they expand roads with each additional project. [18]

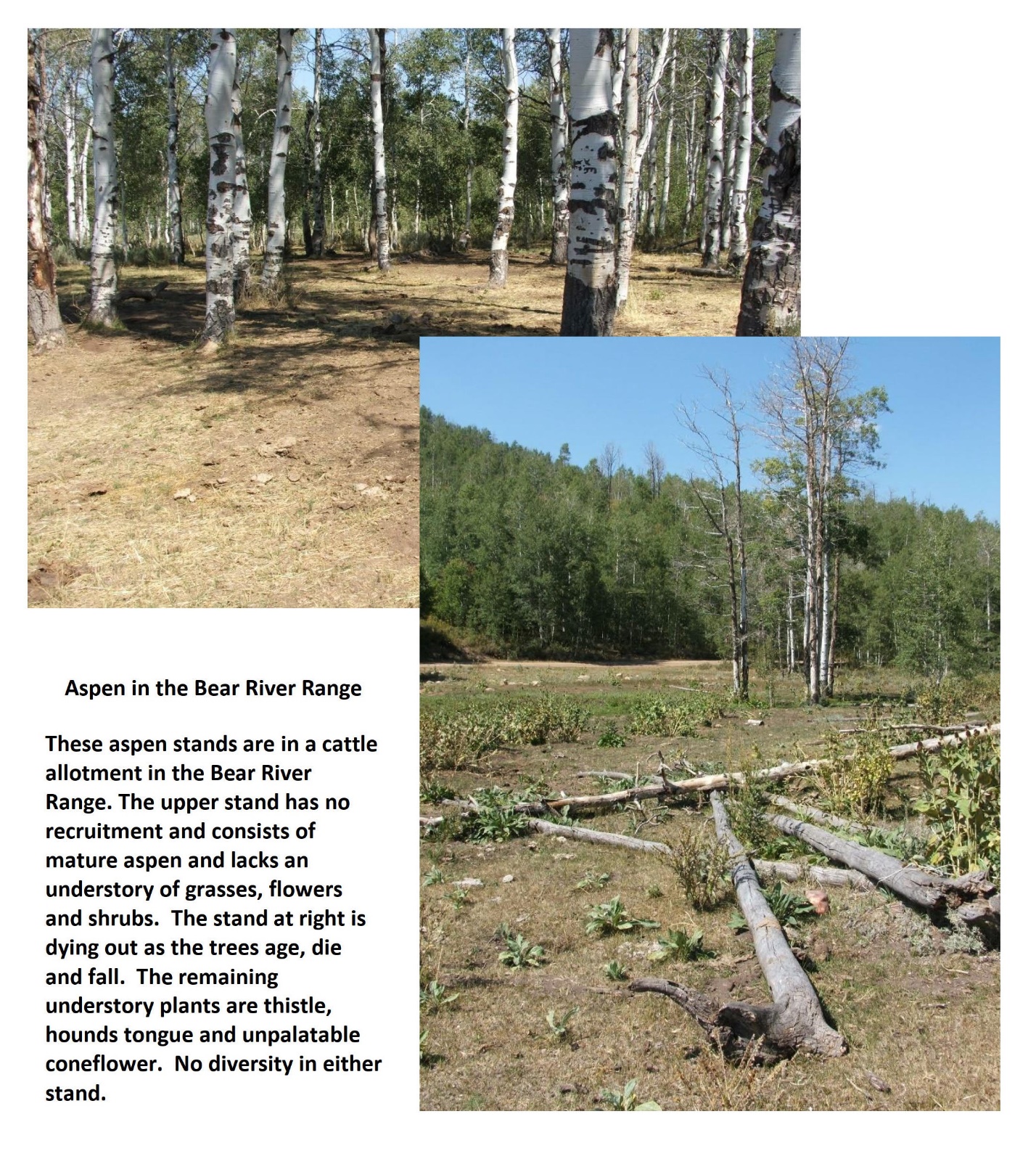

We have studied the Bear River Range over the decades as it was where we first became aware of the terrible damage inflicted by sheep and cows permitted to graze on our National Forests and which the Forest Service always deflects around. They tell us we don’t know the difference between “use and abuse”, they conflate livestock with elk and deer by using the term, “ungulates” to describe them while it is the cattle and sheep that are the overwhelming consumers of plants and browsers of aspen shoots. [19] Streams with barren banks are polluted with E.coli, sediment and manure. Aspen stands lack recruitment, their understories are reduced to bare dirt and they eventually die off, or are dominated by conifers as the grazing promotes accelerated conifer recruitment by eliminating the grasses, flowers and aspen that would provide ground cover and competition for conifer seedlings.

Beginning in the 1980’s and in the years since, we have documented the problems in this mountain range and its habitat from livestock grazing. In the 1990’s the Forest Service was assessing conditions in Region 4 National Forests, which includes the Bear River Range. At the time, they acknowledged vegetation and habitat problems with large departures from potential conditions for aspen, conifer, sagebrush/grasslands, riparian and wetland areas. They found livestock grazing and past timber harvest were a fundamental cause leading to these departures, yet we have seen no effort to address these causes. At the time, we began to characterize and report on the impacts due to grazing of livestock. [20]

Beginning in the 1980’s and in the years since, we have documented the problems in this mountain range and its habitat from livestock grazing. In the 1990’s the Forest Service was assessing conditions in Region 4 National Forests, which includes the Bear River Range. At the time, they acknowledged vegetation and habitat problems with large departures from potential conditions for aspen, conifer, sagebrush/grasslands, riparian and wetland areas. They found livestock grazing and past timber harvest were a fundamental cause leading to these departures, yet we have seen no effort to address these causes. At the time, we began to characterize and report on the impacts due to grazing of livestock. [20]

Using the Forest Service characteristics that defined healthy vegetation communities such as forest structural stages and understory plant communities, in 2001 we assessed 310 locations in livestock-accessible areas in the Idaho portion of the Bear River Range. These were generally within one mile of water sources and in areas with less than 30% slope, considered “capable” for livestock. At each location we applied Forest Service criteria for proper functioning condition of the plant communities and habitats. Of these, only 53, or 17% were properly functioning.

We measured habitat structure and ground cover by vegetation at 55 locations in forest openings in sagebrush/grasslands and tall forb communities, finding that bare soil was dominant, averaging over 50%. Potential ground cover is over 90% and in most habitats near 100%. In the Utah portion of the Bear River Range we conducted additional surveys over time. We compared ground cover in grazed vs ungrazed habitats showing ground cover less than 50% in those areas grazed by cattle or sheep. When we grouped the sites by management type, forested areas that were logged and grazed had only 60% ground cover as compared to the forest openings in sagebrush/grassland at 40% and ungrazed controls over 90%. In the logged and grazed areas, woody debris made up the difference. This loss of ground cover has implications for watersheds in that greater bare soil leads to accelerated erosion, loss of infiltration and ground water recharge, more rapid runoff and flooding, and stream flow depletion in summer.

These allotments all contained large numbers of stock ponds and water troughs for livestock, a proposition the Forest Service promotes time after time as a solution to overgrazing in areas already accessible to water. In one allotment alone, there were 130 stock ponds or water troughs and these are the conditions we found. We looked further at the impacts of these water sources by sampling areas at different distances from the water source, finding that sites closer to water were more heavily grazed (less ground cover) and had lower soil carbon, nitrogen and reduced litter depth when compared to sites with lesser or no grazing. The grazed sites also had lost most or all of the mycorrhizal fungi layer which is fundamental to nutrient cycling. [21]

Conclusion

Even if prescribed fires could provide a benefit, the benefits would be negated if livestock remain and continue to destroy our aspen communities, denude and pollute our streams and springs, and create thickets of conifer saplings. The Forest Service continues business as usual and is budget-driven to propose projects such as these 2,000,000 acres of prescribed fire and vegetation manipulations because they can fit into the wildfire program. [22]

This fire-driven set of priorities must change. The Forest Service must recognize the contribution of timber harvest and livestock grazing to loss of carbon storage in plant communities and soils, increased carbon emissions, and degradation of wildlife habitat. It must define, protect and restore wildlife migration corridors. It must act to reduce road density with its associated motorized recreation, and greatly reduce or eliminate livestock grazing thru permit action and mechanisms such as voluntary permit retirement and buyouts. Until this happens, Forest Service managed lands will remain in the lowest protection status while continuing to exacerbate carbon loss and climate change.

The post Protecting 30% of Our Lands by 2030: Are National Forests “Protected”? appeared first on CounterPunch.org.