This story was produced in collaboration with Newsy

The town of Picher, Oklahoma, on the Quapaw reservation, is home to one of the largest Superfund sites in the United States. Tar Creek, which feeds into the Neosho River then on to Grand Lake, runs gold with zinc. Underground reservoirs seep lead-tainted water and other toxic chemicals when it rains. Trees along the waterway have turned shades of orange near their roots where a steady flow of chemicals have oxidized and crusted over. On the landscape, gray piles of silicone, dolomite, and limestone waste stand two to three stories high. In 1994, the Indian Health Service reported that 34 percent of Native American children in the area had lead concentrations in their bloodstream well above the federal limit — a lasting legacy after more than a century of mining for zinc and lead at multiple sites on the reservation.

“It’s everywhere,” said Quapaw Nation Secretary Treasurer Guy Barker. “Trace amounts of lead within drinking water, groundwater — it’s also in the air. It’s blowing around, it’s in the ground soils in the sandbox that the kids are playing in.”

Mining ended in the 1970s, and in 1983, the Environmental Protection Agency named the 40 square miles around Picher a Superfund site. Beginning in 2005, the state of Oklahoma offered buyouts of homes to relocate families, including many Quapaw citizens, to safer areas, and by 2010, the EPA also began buyouts while contracting with companies to conduct cleanup.

In 2012, the Quapaw Nation took over soil remediation efforts and cleanup with a multi-million dollar contract from the EPA, removing large piles of mining waste and rehabilitation of the land. But last year, a decade after the Quapaw took on the cleanup, the Supreme Court ruled that nearly all of Eastern Oklahoma was an Indian reservation, raising absorbing questions about environmental jurisdiction in the region.

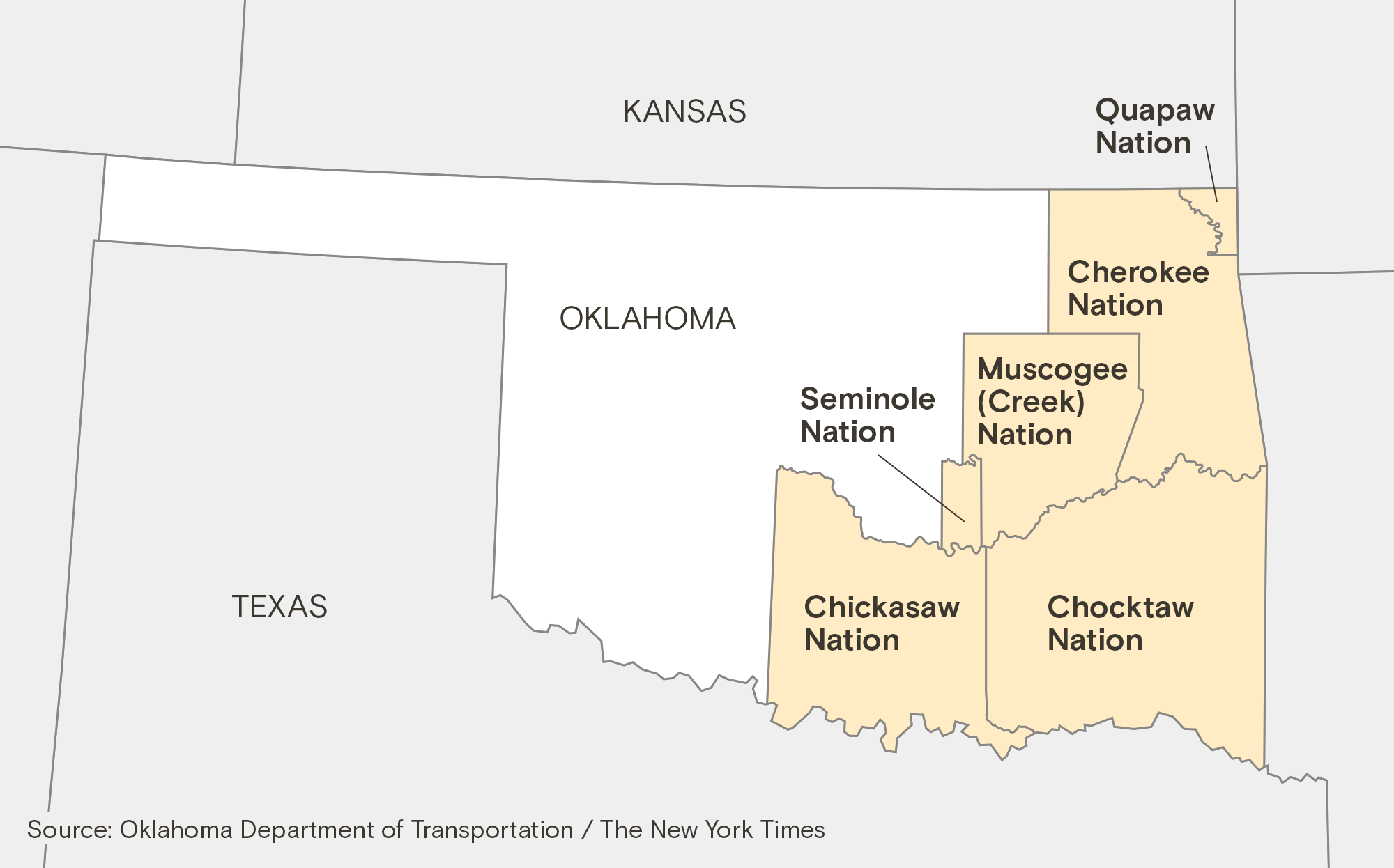

In 2018 and 2019, the Supreme Court agreed to hear McGirt v. Oklahoma, which involved Jimcy McGirt, who committed sex crimes and challenged his conviction, saying that Oklahoma never had the right to prosecute because his crimes were committed within the Muscogee Nation. McGirt, a Seminole Nation citizen, said that only the federal government could prosecute his cases since they happened in Indian territory. The question at the heart of the case was whether or not the Muscogee Nation’s reservation still existed. With statehood in 1907, Oklahoma believed that the reservation was disestablished. The Supreme Court disagreed and found that Congress, the only body with the authority to terminate the tribe’s reservation, had never disestablished it — even after Oklahoma became a state.

The decision was viewed as a win for tribal sovereignty and subsequently was applied to the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole Nations in 2021. And shortly after, a lower court in a subsequent case last fall applied the McGirt ruling and found that the Quapaw Nation reservation was never disestablished either.

But while McGirt focused on criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country, there are far-reaching implications, specifically around environmental jurisdiction and whether tribes — and specifically, the six tribes whose reservation lands make up eastern Oklahoma — can now exercise power over environmental policy there, from clean air and water to remediation plans and strip mining.

A recent report by the Indigenous Environmental Network, an Indigenous-led nonprofit focused on protecting the environment, estimates that over the past decade, Indigenous people engaged in defense of land and water “stopped or delayed greenhouse gas pollution equivalent to at least one-quarter of annual U.S. and Canadian emissions.” The United Nations estimates that Indigenous people live in areas that contain approximately 80 percent of the planet’s biodiversity but “still struggle to maintain their legal rights to lands, territories, and resources.” In Oklahoma, the idea that Indigenous people can take the lead on environmental regulation may soon be put to the test.

“What capacity does our environmental office and the tribe have to take on and enforce regulations?” asked Quapaw Environmental Agency Director Craig Kreman. “I think that’s coming into question with McGirt.”

In its most narrow interpretation, the McGirt ruling impacts Oklahoma only. But Cherokee citizen Dylan Hedden-Nicely, the University of Idaho’s Native American Law Program Director, says the detail in the McGirt case is in the court’s interpretation of federal Indian law and what it could mean for broader environmental movements led by Indigenous nations.

“On its face, McGirt is only about Oklahoma,” Hedden-Nicely said. “But what it signaled, at least in my mind, was that the Supreme Court was saying, ‘We’re open for business for tribes.'”

Historically, the Supreme Court has been hostile to Indigenous nations. According to Joel Williams, a staff attorney with the Native American Rights Fund and citizen of the Cherokee Nation, from 1969 to 1986, when Warren Burger served as chief justice, tribal interests prevailed about 58 percent of the time, but under Burger’s successor, William Rehnquist, tribes saw success only 23 percent of the time. In 2005, when Chief Justice Roberts took the reins, Indigenous peoples saw their interests prevail only 11 percent of the time.

But new additions to the court have brought justices with experience in Indian Law and legal minds that appear to be focused on founding principles of Indian law instead of rehashing old court opinions. It’s what experts compare to a “reset” of court values in regards to Indigenous peoples and Indigenous rights, brightly illustrated through McGirt.

“Since roughly the mid-’80s, the odds were just greatly stacked against tribes and tribal interests at the Supreme Court, and we’ve seen a shift,” said Williams. “Tribes, in more recent years, have prevailed at the U.S. Supreme Court about 85 percent of the time. Almost a 180-degree turnaround.”

One reason, Williams says, has been the appointment of justices with strong voting records on Indian law cases. After Antonin Scalia’s death in 2016, for instance, then-president Donald Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch to take his place. While Democrats raised concerns over his judicial record, for tribes, Gorsuch’s upbringing in the West and experience dealing with Indian case law in the 10th Circuit offered potential: Both the Native American Rights Fund and National Congress of American Indians supported the nomination. And where Scalia voted in favor of tribal interests about 16 percent of the time during his tenure, to date, Gorsuch has voted for tribal interests in 89 percent of the cases brought before him and authored the majority decision in McGirt.

One of the many incongruities in Indian Law is that liberal supreme court judges are not always good for Indigenous communities. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, for instance, voted against Indigenous interests in more than half of the cases that came before her, while Justice Breyer, who recently announced his retirement, voted for tribal interests only about 40 percent of the time. “Justice Breyer was no tribal sovereignty warrior à la Sotomayor,” wrote Matthew Fletcher on Turtle Talk, an influential Indian Law blog, “but he was no Indian fighter, either.” Sotomayor, incidentally, has voted for tribal interests 78 percent of the time.

“Neil Gorsuch and Sonia Sotomayor have been the two people that have taken up intellectual leadership in the field of federal Indian law within the court,” said Hedden-Nicely. “Which is sort of funny: Indian law makes for strange bedfellows.”

At the heart of change at the court is the application of the law. Monte Mills, a federal Indian law professor at the University of Montana, said in the past, the court has more or less defaulted toward concerns of disruptions caused by tribes asserting their rights. For instance, in a 2005 case, the Oneida Indian Nation repurchased their traditional lands in upstate New York, but the city of Sherrill, where much of the land was located, tried to make the nation pay taxes. In an earlier case, the Court held that the law was on the side of the Nation and found that the land was illegally taken from them. However, in the Supreme Court’s final 2005 decision, Justice Ginsberg, writing for the majority, sided with the city of Sherrill. Even though the lands had never been legally acquired from the Nation, the majority found that a change in jurisdiction would disrupt the “settled expectations” of non-Indigenous residents. In McGirt, Mills said, the impact of the ruling was not considered, only the law.

”So in that sense, I think McGirt does mark a shift to recommitting to some of those foundational principles: The tribes had the law on their side all along because Congress never did explicitly disestablish these reservations,” said Mills. “So the law wasn’t ever the question — it was whether or not the Supreme Court would follow the law or defer to these practical consequences.”

In his most recent State of the State address, Oklahoma Governor and Cherokee Nation citizen Kevin Stitt said the McGirt decision jeopardizes public safety and that it has harmed both Native and non-Native victims. He and Attorney General John O’Connor have filed more than 40 petitions to the Supreme Court seeking to overturn the decision entirely. Last month, those petitions were denied. However, the U.S. Supreme Court did grant a review of one question: whether the state has concurrent jurisdiction when non-Natives commit crimes on the reservation. That argument will be heard in April.

Only Congress has the power to dissolve tribes, end treaties, and legally terminate the existence of Indian Country — a path officials took from 1953 to 1968. There’s also the possibility of legislatively hamstringing Indigenous power: In 2005, Oklahoma Senator James Inhofe — an outspoken climate denier — slipped a midnight rider into the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act (SAFETEA). At the time, tribes were exploring how to implement environmental programs that were at odds with Oklahoma’s oil and gas industry, and while normally, states have no jurisdiction on tribal lands, the SAFETEA rider allows Oklahoma’s governor to ask the EPA for that exception when it comes to environmental regulation.

Within weeks of the McGirt decision, Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt asked the EPA to utilize that exception — much to the anger of tribal leaders who were given only 30 days to provide feedback. In December 2021, the EPA decided to slow roll the decision, citing more of a commitment to nation-to-nation consultation under the Biden administration.

For the Quapaw Nation, the McGirt ruling means that any company wanting to haul away toxic waste or assist in the cleanup of the Tar Creek Superfund site could be subject to Quapaw’s environmental regulations, not the state’s.

Quapaw Nation officials say it’s probably going to take decades to finish the cleanup and make more of the land in and around Picher usable and to make sure there are no more piles blowing dolomite and silicone waste across the landscape.

Recently, the Quapaw Nation’s Secretary Treasurer Guy Barker and Chairman Joseph Byrd invited Governor Kevin Stitt to visit Picher after the court ruled that their reservation was never disestablished. Stitt still hasn’t visited.

Quapaw leadership is glad the state isn’t in charge of cleanup and that the tribal nation is able to build capacity to have more authority over environmental activity under McGirt. They look around and say that this is what Oklahoma has done for the tribe.

“Come drive around Picher,” said Barker. “See where state stewardship has gotten us.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Who’s in charge of fixing the environment in eastern Oklahoma? on Feb 22, 2022.