The Insiders

In a 2002 interview with the Observer, the BBC’s John Cody Fidler-Simpson CBE of Kabul, to give him his full name and title, was asked to define the ‘essential qualities’ of a journalist. Simpson responded with typical left-field quirkiness:

There’s something slightly wrong with most of us, don’t you feel? We’re damaged goods, usually with slightly rumpled private lives and unconventional backgrounds.

This certainly rings true. In our experience, the average male journalist is pretty much as Bogart described Captain Renault in ‘Casablanca’:

Oh, he’s just like any other man, only more so.

Take the BBC’s Andrew Marr. In his book My Trade, Marr asked himself why he had become editor of the Independent in 1996:

‘So, why had I done it? There were, looking back, two crucial factors in my mind. The first was vanity. The second was greed. To be a national newspaper editor is a grand thing. Even at the poor-mouse Independent, though I didn’t have a chauffeur, I was driven to and from work in a limousine, barking orders down my mobile phone… In the office, I was the commander…’1

Driven by vanity and greed, self-identifying as ‘celebrities’, elite journalists have egos like any other man or woman, only more so.

As we will see, this ego inflation has serious consequences for their willingness to tolerate even polite criticism, much less to admit error, much less to improve their journalism.

Before the rise of social media, rumpled propaganda ne’er-do-wells like Simpson and Marr had been spoiled by decades of near-impenetrable corporate protection. Swatting away token complaints on newspaper letters pages, journalists were used to being applauded, feted, admired. It was all they knew. Like anyone who has been spoiled rotten, they became arrogant, conceited brats.

When we started Media Lens in 2001, we had no particular expectations. We imagined – naively, as it turned out – that if we wrote clearly and politely, using rational arguments based on credible facts and sources, journalists might be willing to engage with us in ways that readers would find intriguing and eye-opening.

While this occasionally did happen in the first few years, we were more often astonished by the petulant, abusive nature of the responses. Like an oversized, tantruming toddler, Roger Alton, then editor of the Observer (and subsequently Independent editor), screeched at one polite emailer:

Have you just been told to write in by those cunts at medialens? Don’t you have a mind of your own?2

It’s probably not wild speculation to suggest that Alton was the ‘senior journalist’ who anonymously described us to a BBC reporter as ‘poisonous cunts’.3

When we politely asked Guardian cartoonist Martin Rowson to explain the basis for a cartoon he had drawn on the Syrian conflict, toys flew to all corners of the room:

[Media Lens] has succeeded in riling me. Well done. If I’m proved worng [sic] I’ll apologise. Meanwhile, fuck off & annoy someone else… No time for this anymore. Sorry. I stand convicted as a cunt. End of …4

Journalists with more self-restraint have worked hard to smile through gritted teeth, dismissing our arguments with surreal ‘humour’. In 2005, we challenged John Rentoul, chief political correspondent at the Independent on Sunday, and currently a visiting professor at King’s College, London, about his dismissal of the first Lancet study into Iraq mortality following the 2003 invasion. His sage reply:

Oh no. You have found me out. I am in fact a neocon agent in the pay of the third morpork of the teleogens of Tharg.5

The BBC’s John Sweeney stuck out his tongue from the same playground:

David Edwards and David Cromwell of MediaLens – a fancy name for two moonlighting clerks from the White Fish Authority or some such aquatic quango [in fact, one of us, DC, was then a scientist at the National Oceanography Centre] – berate me for fiddling with the facts about the effect of Saddam’s chemical weapons on the Iraqis.

On 7 June, 2004, presenter Jon Snow observed in that day’s Snowmail news digest from Channel 4 News:

Ronnie Reagan lies in state. Particular pangs for me I must admit, having been ITN’s Washington correspondent in the creamier moments of Ronnie’s reign. The great eulogies seem to evade the moments of madness.

We wrote to Snow:

Hi Jon

Yes, and beyond “the moments of madness”, the eulogies also seem to evade the years of searing, barely believable torture and mass murder in places like Nicaragua, East Timor, and El Salvador. We’ll be watching at 7:00, but we won’t hold our breath…

Best wishes

DE and DC

Blood clearly up, Snow’s index fingers raged across his keyboard in response:

you cynics! If you’d been around at the time you’d have seen me exposing his outrages in central america..you may think i’m a sell ouyt [sic] these days but i can assure u, I have been there..

In the wake of Jeremy Corbyn’s stunning election performance in June 2017, Snow introduced Channel 4 News with the fitting words:

Good evening. I know nothing. We, the media, the pundits, the experts, know nothing.

Just one month later, Snow made an extraordinary, 180-degree volte face:

I think this is the golden age for journalism. First of all, it’s sorted the wheat from the chaff. The people who sat around at the back of the office and pumped out the occasional obituary have fallen by the wayside. But if you’re up for it, in what used to be the conventional media, you’ve a fantastic future.

Like almost every other high-profile corporate journalist, Snow’s endless self-contradictions and queasy, career-protective contortions remind us of Groucho Marx’s comment:

Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them…well, I have others.

The great flaw in John Simpson’s analysis was his additional comment on the ‘essential qualities’ of journalists. They were, he said: ‘Outsiders, looking in at others from outside’.

In fact, journalists are the ultimate corporate insiders looking out at a world to be manipulated and pacified from the heart of Elite Media Club. Journalism, particularly broadcast journalism, is far too important to people with power for it to be any other way.

In what follows – partly for fun, but also to highlight the dearth of serious discussion on the ‘mainstream media’ in the ‘mainstream media’ – we have collected some remarkable replies from journalists. Where possible, we have linked back to the original discussions so that you, dear reader, can make of them what you will.

Andrew Marr Promises Not To ‘Bother With “Media Lens”’ Ever Again

In 1999, Andrew Marr, a former editor of the Independent who was by then an Observer columnist, had spoken out in support of Tony Blair’s crazed call for a ground invasion in the former Yugoslavia. In the Observer under the title, “Do we give war a chance?“, Marr had proclaimed:

I want to put the Macbeth option: which is that we’re so steeped in blood we should go further.

The following week, Marr’s Observer column was titled, ‘War is hell – but not being ready to go to war is undignified and embarrassing’. He referred to the ‘war-hardened people of Serbia’ and called them ‘beasts’, explaining that the Serbs, ‘far more callous, seemingly readier to die, are like an alien race.’

We cited the above battle cry in a media alert on 3 October, 2001. Marr, who had since become the BBC’s political editor, wrote an email to us in response:

I’m afraid I think it is just pernicious and anti-journalistic. I note that you advertise an organisation called Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting so I guess at least you have a sense of humour. But I don’t think I will bother with “Media Lens” next time, if you don’t mind.

We replied to Marr, rebutting his crass jibe of ‘pernicious and anti-journalistic’, and defending our analysis of his articles. But, true to his word, Marr has ignored us ever since. We have not forgotten about the BBC man, however. His BBC career may well be defined by the clip of him outside 10 Downing Street reporting for BBC News at Ten on 9 April, 2003. He had been asked by presenter Huw Edwards to describe the significance of the fall of Baghdad to the invading US forces.

Frankly, the main mood [in Downing Street] is of unbridled relief. I’ve been watching ministers wander around with smiles like split watermelons.

Marr’s happy smile mirrored those of the government ministers he had observed. He continued:

I don’t think anybody after this is going to be able to say of Tony Blair that he’s somebody who is driven by the drift of public opinion, or focus groups, or opinion polls. He took all of those on. He said that they would be able to take Baghdad without a bloodbath, and that in the end the Iraqis would be celebrating. And on both of those points he has been proved conclusively right. And it would be entirely ungracious, even for his critics, not to acknowledge that tonight he stands as a larger man and a stronger prime minister as a result.

This was a remarkable demonstration of the propaganda function of corporate journalists, not least the role of the political editor of BBC News. Marr had risen to those heady heights because he had demonstrated for years that he could be trusted as a safe pair of hands.

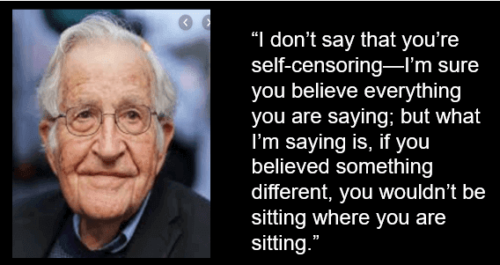

Ironically, in 1996, while he was still at the Independent, Marr had interviewed Noam Chomsky for the BBC2 series ‘The Big Idea’. Marr had been dismissive of the propaganda model and simply could not understand that journalists were not the crusading, adversarial truthtellers standing up to power that he believed them to be. ‘How can you know that I’m self-censoring?’, asked an incredulous Marr. Chomsky replied:

‘I’m not saying you’re self-censoring. I’m sure you believe everything you say. But what I’m saying is if you believed something different you wouldn’t be sitting where you’re sitting.’

Exactly.

Clones R Us

In 2002, we examined the BBC series ‘The Century of the Self’ which focused on the public relations guru Edward Bernays who had famously coined the term, ‘engineering of consent’. Bernays’ ideas, building on Freud’s theories about human psychology, were deployed by the rapidly growing corporate advertising industry in the 20th century to boost profits. The series was written and produced by the BBC’s Adam Curtis, and attracted considerable attention and acclaim.

We admired aspects of the series, including its clever use of visuals and somewhat sardonic voice-over, but we pointed out that much crucial information was missing from Curtis’s analysis. This was especially noticeable when it came to serious omissions regarding the destructive role of big business and how the ‘threat of Communism’ was used to ‘justify’ US foreign policy to undermine democracy and independent nationalism in Chile, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, Haiti, Iran, Indonesia, Vietnam and elsewhere around the world.

As described in a follow-up media alert, we summarised our observations in a polite email to Curtis and then, not hearing from him, followed up with a gentle nudge. We received this peeved reply from Curtis the same day:

I don’t know whether it occurred to you that I might have been away – instead of stamping your little feet and trying to whip up an attack of the clones. I’ve just read your piece – thanks and I’ll reply to it on Thursday if that’s ok? I’ve got to be filming before then.

The dismissal of public criticism as coming from unthinking ‘clones’ was ironic, given the subject matter of his documentary. To be fair to Curtis, he did indeed reply soon after and we wrote about the subsequent exchange in another follow-up media alert.

‘Evidence-Based Journalism’

Over a number of years, we repeatedly challenged the BBC on its deeply skewed, US-UK-driven propaganda coverage of Iraq. In 2004-2005, we drew particular attention to the BBC’s soft-pedalling of the brutal US assaults on Fallujah, Iraq (for example, here and here).

Back in the days when senior BBC News editors and correspondents engaged directly, sometimes at length, with Media Lens, we received this reply from Helen Boaden, then head of BBC News:

We are committed to evidence-based journalism. We have not been able to establish that the US used banned chemical weapons and committed other atrocities against civilians in Falluja last November [2004]. Inquiries on the ground at the time and subsequently indicate that their use is unlikely to have occurred.

In fact, atrocities had taken place and banned chemical weapons – specifically, white phosphorus – had been used. But the BBC consistently ignored or downplayed credible testimony from multiple sources. BBC correspondent Paul Wood, who had been embedded with US forces in Fallujah, and who had failed to report the enormity of their crimes, excused himself and the BBC with these words:

We didn’t at the time, last November, report the use of banned weapons or a massacre because we didn’t see this taking place – and since then, we haven’t seen credible evidence that this is was [sic] what happened.

Wood had earlier dismissed reports of the use of banned weapons in Fallujah on the grounds, Boaden told us, that no ‘reference [was] made to them at the confidential pre-assault military briefings he attended.’ When we pressed Boaden, citing further independent reports of atrocities committed against civilians, she abruptly ended the correspondence:

I do not believe that further dialogue on this matter will serve a useful purpose.

As we have seen in the intervening years, the attitude of BBC News to our challenges is now essentially:

I do not believe that any dialogue on this matter will serve a useful purpose.

BBC ‘Impartiality’ = Accepting And Broadcasting Western Leaders’ Claims

As many readers will recall, BBC propaganda leading up to the invasion of Iraq, and the subsequent US-led occupation, was unceasing. For example, on 22 December, 2005, Paul Wood told millions of BBC News at Ten viewers:

The coalition came to Iraq in the first place to bring democracy and human rights.

When we asked Helen Boaden if she realised this version of US-UK intent compromised the BBC’s claimed commitment to impartial reporting, she replied:

Paul Wood’s analysis of the underlying motivation of the coalition is borne out by many speeches and remarks made by both Mr Bush and Mr Blair.

But Wood was not merely describing Bush and Blair’s version of events. That would have involved him saying: ‘The coalition claims that it came to Iraq in the first place to bring democracy and human rights.’ Instead, he was stating his own opinion on why the coalition ‘came to Iraq’.

When we emailed Boaden again in January 2006, she replied:

To deal first with your suggestion that it is factually incorrect to say that an aim of the British and American coalition was to bring democracy and human rights, this was indeed one of the stated aims before and at the start of the Iraq war – and I attach a number of quotes at the bottom of this reply.

Remarkably, Boaden had attached no less than 2,700 words of propaganda quotes from George Bush and Tony Blair, amounting to around six single-spaced A4 pages, in a facile attempt to ‘prove’ her point.

If we are to take Boaden’s comments at face value, she was arguing that Bush and Blair must have been motivated to bring democracy to Iraq because they had said so in speeches! ‘Impartial’ BBC reporting means that we should take our leaders’ claims on trust.

‘No Need For A Mea Culpa. We Did Our Job Well’

In 2004, we presented an overview of how several of the corporate news media had covered the build-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the war itself; namely, served as propaganda outlets for Western power. In contrast to the limited mea culpa of the New York Times, all the UK news media we approached rejected the notion that they had done anything seriously wrong or performed poorly in terms of their stated public commitment to fair and accurate journalism. Perhaps the most breezily deluded response came from David Mannion, then Head of Independent Television News:

The evidence suggests we have no need for a mea culpa. We did our job well.

In an important sense, of course, Mannion was correct. Given that the primary function of the corporate media is to channel and amplify propaganda from sources of power – especially Washington and London – they did indeed do ‘our job well’.

Robots R Us

In response to our media alert, “The Media Ignore Credible Poll Revealing 1.2 Million Violent Deaths In Iraq, published on 18 September, 2007, BBC Newsnight presenter Gavin Esler sent the following response to one of several Media Lens readers who had contacted him politely:

Sorry but this medialens inspired stuff is very sophomoric. The last time I remember a robotic response from people like this was watching film of the nuremberg rallies. I always wondered why people marched to another’s beat without any obvious thought from themselves. Perhaps you know the answer, or perhaps you merely intend to keep marching.

Please don’t write to me again in someone else’s words. It is so embarrasing [sic] for you. Please learn to think for yourself.

Gavin

Esler’s ‘robotic’ respondents were, in fact, members of the public who cared enough about the devastating impact of corporate media bias to spend time writing to journalists. The polite and thoughtful email that elicited this response was sent by an MA student at Durham University. You can read his email here.

‘Dear Serviles’

In 2002, we challenged the Observer’s Nick Cohen about his misleading comments on UN sanctions against Iraq, and his persistent cheerleading for a US-led invasion that would take place the following year. Cohen had absolved the West of all responsibility for the horrendous death toll in Iraq under UN sanctions. As we noted, these sanctions were responsible for the deaths of around half a million children under the age of five, as documented by Unicef. Denis Halliday and Hans von Sponeck, former UN Humanitarian Coordinators in Baghdad, had both resigned, one after the other, in protest at the ‘genocidal’ impact of UN sanctions. These mass-death sanctions had been maintained with great remorselessness by Washington and London, supported by a propaganda barrage that was faithfully relayed by corporate news media. But Cohen attributed all the blame for the death toll on Iraq’s leader, Saddam Hussein, slavishly sticking to the official narrative. Cohen emailed us back in high dudgeon, addressing us as ‘Dear Serviles’, concluding with what he no doubt considered a hilarious and crushing rejoinder, ‘Viva Joe Stalin’.

‘All The Bloody Children’

When one Media Lens reader, an 83 year-old WW2 veteran, offered a polite and considered rebuttal to the propaganda distortion carried in the Observer on UN sanctions against Iraq, editor Roger Alton emailed back in exasperation:

This is just not true … it’s saddam who’s killing all the bloody children, not sanctions. Sorry

To paraphrase Chomsky, ask yourself: would a journalist who thought any differently ascend to the throne of Observer or Independent editor?

‘A Curious Willy-Waving Exercise’

Peter Beaumont, foreign affairs editor of the Observer, objected so much to our critical appraisal of his review of a book by Noam Chomsky in 2006 that he devoted a column to attacking Media Lens:

It is a closed and distorting little world that selects and twists its facts to suit its arguments, a curious willy-waving exercise… Think a train spotters’ club run by Uncle Joe Stalin.

In resurrecting Stalin, Beaumont may have been inspired by his Observer colleague’s previous ‘witticism’ (see Nick Cohen above). It is left to the imagination of the reader why a supposedly serious journalist, at a supposedly serious newspaper, should feel the need to depict an exchange of views as ‘willy-waving’.

‘Most Prejudiced And Blinkered’

In 2006, the BBC’s John Simpson took exception to our challenge that BBC News could be rationally considered ‘impartial’:

It takes an enormous act of will to believe that [BBC News protects established power] nowadays, and only the most prejudiced and blinkered person could possibly manage to do it — but you’re prepared to make the necessary effort.

Our examples in the email exchange with Simpson focused on the BBC’s pro-Bush/Blair coverage of Iraq which had consistently minimised or ignored solid evidence of US-UK war crimes, as we saw earlier. Simpson, along with his BBC colleagues, had seemingly made ‘the necessary effort’ not to dwell on those war crimes.

In our reply to Simpson, we noted that his comment was an exact reversal of the truth: ‘only the most prejudiced and blinkered person’ could possibly manage to believe that the BBC does not act as a mouthpiece for powerful interests.

‘The John Motson Approach To Analysing News’

In 2011, we attempted to debate BBC News coverage of the Middle East with Paul Danahar, then the BBC Middle East Bureau Chief, based in Jerusalem (he is currently the BBC’s North America Bureau Chief).

We started by asking Danahar to address the careful studies by Greg Philo and Mike Berry, of the renowned Glasgow University Media Group, and published in their book, More Bad News From Israel ((Pluto Press, 2011.)) Philo and Berry’s careful work demonstrated that BBC News strongly favours the Israeli perspective over the Palestinian perspective.

Recall that between December 2008 – January 2009, Israeli forces mounted a massive campaign of violence against Gaza in Operation Cast Lead. Israel’s leading human rights group B’Tselem estimated that 1,391 Palestinians were killed, including 344 children. In addition to the large numbers of dead and wounded, there was considerable damage to Palestinian medical centres, hospitals, ambulances, UN buildings, power plants, sewage plants, roads, bridges and civilian homes. The BBC later refused to broadcast a charity appeal on behalf of the people of Gaza, an almost unprecedented act in BBC history. In a live BBC interview, Tony Benn famously defied the ban.

In our exchange with Danahar, we gave a summary of Philo and Berry’s detailed statistical findings for BBC News coverage of Operation Cast Lead. Quoting Philo and Berry, we noted that the BBC perpetuated ‘a one-sided view of the causes of the conflict by highlighting the issue of the rockets without reporting the Hamas [peace] offer’ and by burying rational views on the purpose of the attack: namely, the Israeli desire to inflict collective punishment on the Palestinian people.

Apparently in all seriousness, Danahar responded to us:

I wasn’t around during Cast Lead I was in China. So my main observation would be a personal one and that is that I’m not a big fan of the John Motson approach to analysing news.

We, of course, recognised the name of the legendary BBC football commentator, but we asked Danahar to clarify exactly what he meant by ‘the John Motson approach to analysing news’. He replied:

Personally, I don’t think adding up the number of sentences about coverage is much more useful, when comparing two news organisations [BBC and ITV], than trying to work out who has won a football match by counting how many times one team kicked the ball compared to the other.

In fact, Philo and Berry’s comparison was about the relative weight afforded to the Israeli and Palestinian perspectives, not the relative performances of the BBC and ITV. We asked Tim Llewellyn, who had spent ten years as a BBC Middle East correspondent, if he had a response to Danahar’s comment:

I like the John Motson reply. Given that counting lines is EXACTLY (to the milli-second) how the BBC reckons up “balance” in election reporting in the UK, they must believe themselves in the Motson approach as an act of Reithian Faith. But your point is the right one, that line-counting is not what counts so much as BBC news content, which as [Philo and Berry’s book, More Bad News From Israel] finds scientifically and we journalists who observe both the BBC and the Middle East have known for the past ten years or so, reflects to a massive degree the Israeli perspective and fails to report properly the Palestinian plight, the Palestinians’ view of the real causes of the tragedy and how they are forced to react to it, the context of the whole struggle and real cause and effect.6

Danahar then became ever more evasive in our exchange, presumably believing that flippancy was the best approach when presented with factual analysis:

I think it’s a little harsh to suggest that “Bad news from Israel” is an essential read. It’s placed 251,456 on the best seller list at Amazon a full 61,238 places behind “How to defend yourself against Alien Abduction” though the latter is more reasonably priced so maybe that helped its sales.

As so often happens, what had begun as a sincere discussion on the part of Media Lens, at least, had now become farcical. Danahar revealed that he had little intention of addressing the serious issues put to him. The conversation ended with increasingly odd burblings from the senior Jerusalem-based BBC journalist (the full emails are archived here in our forum).

‘Do you guys not have bosses?’

In March 2013, Mehdi Hasan, then Huffington Post UK’s political director, published a fascinating, if bizarre, response on Twitter after we had pointed out the compromises even the ‘best’ journalists and commentators have to make to retain a platform in the ‘mainstream’ media. He tweeted in seeming confusion:

Sorry, in which world is it acceptable for employees to publicly attack or critique their employers? Do you guys not have bosses?

We replied:

No, we don’t have bosses, owners, oligarchs, advertisers, or wealthy philanthropist donors. We’re independent. How about you?

Hasan apparently could not grasp that Media Lens is not beholden to corporate paymasters in an ad-dependent, corporate-owned media in which profit is the bottom line. We were, of course, pointing out that in ‘the real world’ where Hasan worked, ‘free press’ journalists are not free to criticise current or potential employers.

Hasan has since deleted his tweet.

Owen Jones

Owen Jones, perhaps along with George Monbiot, the last remaining and sadly withering leftist fig-leaf at the Guardian, once declared us as bad as the corporate media:

You are as guilty of dishonesty by omission as the mainstream media you supposedly critique.

Why did he attack us in this way? We had pointed out that Jones had conformed to the Western propaganda narrative on Libya in welcoming the Nato-driven removal of Gaddafi. In particular, we had highlighted these words from Jones in 2011 as the US-led destruction of Libya, with UK participation, loomed:

I hope it’s game over for Gaddafi. A savage dictator once tragically embraced by some on left + lately Western governments and oil companies.

Our point was that corporate media leftists like Jones had joined the ‘mainstream’ chorus welcoming regime change in Libya, while claiming to oppose regime change by the Western political leaders that were leading the chorus. It was an absurd and illogical, not to mention immoral, position to take.

Jones has since blocked us on Twitter.

Nick Robinson’s History Book

On 18 June, 2014, we emailed Nick Robinson, then BBC political editor, with whom we had previously corresponded:

Hello Nick,

Did you really say this on BBC News at Ten last night:

‘”The history of the rift between the US and Iran goes all the way back to the Islamic Revolution 35 years ago”?

It sounds like your history book only goes back to 1979. How else can we explain your omission of the 1953 Iranian coup, orchestrated by the US – with British help?

Best wishes

David Cromwell

On 23 June, we received an email on his behalf – presumably from his over-worked personal assistant – thanking us for our email and telling us:

I’ve passed your comments onto Nick. I hope you understand as he receives an overwhelming amount of correspondence he is unable to respond to all letters individually.

We were somewhat miffed not to hear from Nick personally, especially as he had seemed so grateful when we had provided him with the source of a quote by Lord Reith, founder of the BBC, for Robinson’s 2013 book, Live From Downing Street. Ironically, the quote, taken from Lord Reith’s diary and written during the 1926 General Strike, was:

They [the government] know they can trust us not to be really impartial.

That remains an accurate description of BBC News performance to this day.

Concluding Remarks

Twenty years on from founding Media Lens, by using rational, sober, politely-worded challenges, we have managed to alienate a whole slew of prominent editors and journalists, including a few supposedly on ‘the left’. They rarely respond to our critical analyses published on our website – and often republished elsewhere – or to our widely-shared challenges on social media. Many have even blocked us on Twitter. These include Huw Edwards, Jeremy Bowen, Alan Rusbridger, Jon Snow, George Monbiot, Owen Jones, Frank Gardner, Julian Borger and Stephen Pollard. As a long-term experiment, it has been eye-opening for us and, we hope, for our readers.

Rather than seeing this dismissive treatment by corporate journalists as in any way dispiriting, we should regard it as evidence of the power of cogently-argued public challenges to the ‘mainstream’. Moreover, readers would be surprised by just how many high-profile journalists actually support us in private. They thank us for opening their eyes and inspiring them, for keeping them honest, sending us strong praise and encouragement to continue. It says so much about the state of our ‘press freedom’ that these journalists are afraid to support us openly.

- Marr, My Trade: A Short History of British Journalism, Macmillan, 2004, pp. 190-191.

- Email forwarded to us, 1 June, 2006.

- Posted by then BBC journalist David Fuller, Media Lens messageboard, 15 May 2006.

- Rowson, Twitter, 28 May 2012; see his tweets here and here.

- Email, 15 September, 2005.

- Email to Media Lens, 20 May, 2011.