SciCheck Digest

Stanford Medicine says it “strongly supports the use of face masks to control the spread of COVID-19.” Yet viral stories falsely claim a “Stanford study” showed that face masks are unsafe and ineffective against COVID-19. The paper is a hypothesis, not a study, from someone with no current affiliation with Stanford.

Full Story

Evidence indicating that face masks can help control the spread of the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 has grown since the virus first emerged, upending life around the world. In March, we outlined the evolving research on the efficacy of face masks and explained why experts support their use.

But a stubborn thread of misinformation falsely claiming that masks do not work, and are actually dangerous, continues to be recycled and shared a year-plus into the pandemic.

Viral headlines in recent days have wrongly purported that a “Stanford Study” proved that masks are ineffective and dangerous. In reality, the paper in question was one author’s hypothesis and didn’t come from anyone currently affiliated with the university.

“Stanford Study Results: Facemasks are Ineffective to Block Transmission of COVID-19 and Actually Can Cause Health Deterioration and Premature Death,” reads an April 19 headline from the Gateway Pundit, a conservative website known for spreading misinformation. The story — shared on Facebook nearly 28,000 times, according to CrowdTangle analytics data — cites another website, NOQ report, whose story was published two days earlier.

The American Conservative Movement website similarly ran the headline, “Stanford study quietly published at NIH.gov proves face masks are absolutely worthless against Covid.” It was shared on Facebook more than 10,000 times.

The paper being referenced was not an original “study,” but one person’s hypothesis — or proposed explanation — based on a review of some previous literature. It was first published online in November by the journal Medical Hypotheses, which describes itself as “a forum for ideas in medicine and related biomedical sciences.” While the paper appears on PubMed Central — an archive of scientific literature run by the National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine — that does not indicate NIH endorses or concurs with the content, as some of the viral stories wrongly suggest.

The paper’s author, Baruch Vainshelboim, is listed as being affiliated with the “Cardiology Division, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System/Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, United States.”

But Julie Greicius, a spokesperson for Stanford Health Care and the university’s School of Medicine, told us in an email that “[t]he author’s affiliation is inaccurately attributed to Stanford, and we have requested a correction” from the author and the journal.

“The author, Baruch Vainshelboim, had no affiliation with the VA Palo Alto Health System or Stanford at the time of publication and has not had any affiliation since 2016, when his one-year term as a visiting scholar on matters unrelated to this paper ended,” she said in an email. She also noted that “Stanford Medicine strongly supports the use of face masks to control the spread of COVID-19.”

A spokesperson for VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Michael Hill-Jackson, also told us in an email that “Baruch Vainshelboim does not work for the VA and is incorrectly affiliated on this website.” He said Vainshelboim “served as a postdoc assistant under one of our researchers from 2015-2016, however, he was never officially employed by VA and his time in this role is completely unrelated to this paper.”

So, no, the paper is not a study from Stanford, as the headlines claim. It’s unclear where Vainshelboim currently works or why the paper featured the incorrect affiliation. We sent him several questions but haven’t heard back.

We reached out to the editor of Medical Hypotheses, Mehar Manku, about Vainshelboim’s paper and he said in an email that the journal was aware of “issues related to the publication in question” and that “[a]ctions are in progress.”

In the paper, Vainshelboim lays out a hypothesis against the utility of masks and concludes that they are “ineffective to block human-to-human transmission of viral and infectious disease such [as] SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19.” It claims at one point, “Due to the difference in sizes between SARS-CoV-2 diameter and facemasks thread diameter (the virus is 1000 times smaller), SARS-CoV-2 can easily pass through any facemask.”

J. Alex Huffman, an aerosol scientist at the University of Denver, told us in a phone interview that the paper betrayed a fundamental lack of understanding of respiratory aerosols.

“Viruses don’t come out of your mouth as naked viruses,” he said. “They come out in liquid drops that are full of mostly water but also some proteins and salts” — and, if someone is sick, virus.

Huffman further said in an email that “there is a wide distribution of particle sizes emitted when people breathe, speak, sing, or cough, but the range is anywhere from tens of nanometers to hundreds of microns. Most of these, even after evaporation, are easily removed by good masks.”

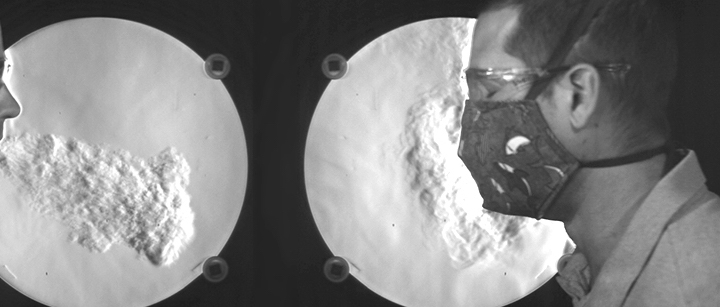

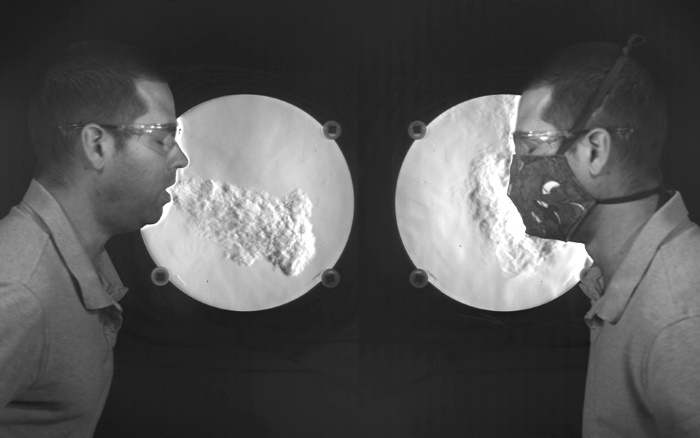

Indeed, lab studies have shown masks can partially block exhaled respiratory droplets, which are thought to be the primary way the virus spreads. Such studies have limitations, but they continue to suggest that masks — especially ones that are multi-layered and fit well — can play a role in stopping the spread of COVID-19.

For example, one study by scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health tested a variety of face coverings for their ability to prevent the outward spread of particles from a simulated cough. N95 respirators performed the best — blocking 99% of the particles — while medical masks blocked 59% and a three-ply cloth mask blocked 51%. (A face shield, on the other hand, stopped just 2%.)

And in another experiment, researchers in Japan evaluated how well different masks on two mannequins that faced one another reduced exposure to the coronavirus. One mannequin was connected to a nebulizer, which produced a simulated cough, “mimicking a virus spreader,” and the other was connected to an artificial ventilator to simulate breathing. If both mannequins wore a cotton or surgical mask, transmission decreased by 60% to 70%.

For more information on the research surrounding face masks, see our SciCheck story “The Evolving Science of Face Masks and COVID-19.”

Vainshelboim’s paper also claims that masks “restrict breathing, causing hypoxemia and hypercapnia.” Hypoxemia is the term for insufficient oxygen in the blood; hypercapnia is the presence of too much carbon dioxide in the bloodstream.

Experts have repeatedly rebuffed that claim, and we’ve previously addressed unfounded claims that masks cause unsafe oxygen levels.

“For many years, health care providers have worn masks for extended periods of time with no adverse health reactions,” the Mayo Clinic Health System notes. “The CDC recommends wearing cloth masks while in public, and this option is very breathable. There is no risk of hypoxia, which is lower oxygen levels, in healthy adults. Carbon dioxide will freely diffuse through your mask as you breathe.”

The American Lung Association also notes: “We wear masks all day long in the hospital. The masks are designed to be breathed through and there is no evidence that low oxygen levels occur.” (However, it recommends that people with preexisting lung disease contact a doctor before wearing an N95 respirator.)

Editor’s Note: Please consider a donation to FactCheck.org. We do not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, 202 S. 36th St., Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Sources

Frodl, Kimberly. “Debunked myths about face masks.” Mayo Clinic Health System. 10 Jul 2020.

Greicius, Julie. Spokesperson, Stanford Health Care. Email to FactCheck.org. 21 Apr 2021.

“Guidance for Wearing Masks.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated 19 Apr 2021.

Hill, David G. “From the Frontlines: The Truth About Masks and COVID-19.” American Lung Association. 18 Jun 2020.

Hill-Jackson, Michael. Spokesperson, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System. Email to FactCheck.org. 21 Apr 2021.

“How COVID-19 Spreads.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated 28 Oct 2020.

Huffman, J. Alex. Associate professor, department of chemistry and biochemistry, University of Denver. Phone interview with FactCheck.org. 21 Apr 2021.

Lindsley, William G., et al. “Efficacy of face masks, neck gaiters and face shields for reducing the expulsion of simulated cough-generated aerosols.” Aerosol Science and Technology. 7 Jan 2021.

Manku, Mehar. Editor, Medical Hypotheses. Email to FactCheck.org. 22 Apr 2021.

McDonald, Jessica. “The Evolving Science of Face Masks and COVID-19.” FactCheck.org. 2 Mar 2021.

Ueki, Hiroshi, et al. “Effectiveness of Face Masks in Preventing Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2.” mSphere. October 2020.

Vainshelboim, Baruch. “Facemasks in the COVID-19 era: A health hypothesis.” Medical Hypotheses. Uploaded online 22 Nov 2020.

The post Stories Falsely Cite ‘Stanford Study’ to Misinform on Face Masks appeared first on FactCheck.org.